Elmore Leonard

Elmore Leonard | |

|---|---|

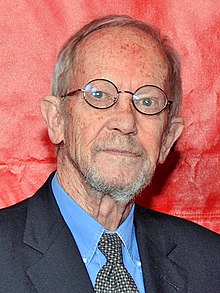

Leonard at the 70th Annual Peabody Awards Luncheon, 2011 | |

| Born | Elmore John Leonard Jr. October 11, 1925 New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Died | August 20, 2013 (aged 87) Bloomfield Hills, Michigan, U.S. |

| Occupation | Writer |

| Alma mater | University of Detroit |

| Genre | |

| Spouse |

|

| Children | 5, including Peter |

| Relatives | Megan Freels Johnston (granddaughter) |

| Military career | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service | |

| Years of service | 1943–1946 |

| Rank | |

| Unit | |

| Battles / wars | World War II |

Elmore John Leonard Jr. (October 11, 1925 – August 20, 2013) was an American novelist, short story writer, and screenwriter. His earliest novels, published in the 1950s, were Westerns, but he went on to specialize in crime fiction and suspense thrillers, many of which have been adapted into motion pictures. Among his best-known works are Hombre, Swag, City Primeval, LaBrava, Glitz, Freaky Deaky, Get Shorty, Rum Punch, Out of Sight and Tishomingo Blues.

Leonard's short story "Three-Ten to Yuma" was adapted as 3:10 to Yuma, which was remade in 2007. Rum Punch was adapted as the Quentin Tarantino film Jackie Brown (1997). Steven Soderbergh adapted Out of Sight in 1998 into a film of the same name. Get Shorty was adapted into an eponymous film in 1995, and in 2017 it was adapted into a television series of the same name. His writings were also the basis for The Tall T, as well as the FX television series Justified and Justified: City Primeval. Among other honors, he won the 2009 Pen Lifetime Award[1] and the 2012 Medal For Distinguished Contribution to American Letters.[2][3]

Anthony Lane of The New Yorker wrote that Leonard

was hailed as one of the best crime writers in the land. High praise, but not quite high enough, and some way off the mark. He was one of the best writers, and he happened to write about crime. Even that is not entirely accurate. It's true that his novels (more than forty of them, with another left unfinished at his death) enjoyed the company of criminals and of those who tried to stop them in their tracks. This was seldom hard, since, as Leonard delighted in showing us, crime—more than anything, even politics—allows men of all ages to disport themselves across the full range of human ineptitude. Boy, do they screw up.[4]

Early life and education

[edit]Leonard was born in New Orleans, Louisiana, the son of Flora Amelia (née Rive) and Elmore John Leonard.[5] Because his father worked as a site locator for General Motors, the family moved frequently for several years. In 1934, the family settled in Detroit. In the 1930s, there were two news items that would influence many of Leonard's works.[6][7] From 1931, until they were killed in May 1934, gangsters Bonnie and Clyde were on a rampage. In 1934, the baseball team the Detroit Tigers made it to the World Series, winning the Series in 1935. Leonard developed lifelong fascinations with sports and crime. He graduated from the University of Detroit Jesuit High School in 1943 and, after being rejected for the Marines for weak eyesight, immediately joined the Navy, where he served with the Seabees for three years in the South Pacific, where he earned the nickname "Dutch", after Tigers pitcher Dutch Leonard.[8] Enrolling at the University of Detroit in 1946, he pursued writing more seriously, entering short stories in contests and submitting then to magazines for publication. He graduated in 1950[9] with a bachelor's degree in English and philosophy. A year before he graduated, he got a job as a copy writer with Campbell-Ewald Advertising Agency, a position he kept for several years, writing on the side.[9]

Career

[edit]Leonard had his first success in 1951 when Argosy magazine published his short story "Trail of the Apaches".[10]: 29 During the 1950s and early '60s, he continued writing Westerns, publishing more than 30 short stories. His debut novel, The Bounty Hunters, was published in 1953 and was followed by four more Westerns. His early work already showed his affection for outsiders and underdogs. He developed his characters through dialogue, each defined by their manner of speech. In many stories, he favored Arizona and New Mexico as settings.[11] Five of his westerns were adapted as movies before 1972: The Tall T (1957), 3:10 to Yuma (1957), Hombre (1967), Valdez Is Coming (1971), and Joe Kidd (1972).

In 1969, his first crime story, The Big Bounce, was published by Gold Medal Books. Leonard differed from well-known names writing in this genre—he was less interested in melodrama than in his characters and in realistic dialogue. He wrote the screenplay for, and the novelization of, Mr. Majestyk (both 1974); Anthony Lane called the latter "the best novel ever written about a melon grower."[4] The stories were often located in Detroit but he also liked to use South Florida as a setting. LaBrava, a 1983 novel set in the latter locale, was praised in a New York Times review, which said Leonard moved from mystery suspense short story writer to novelist.[12] His next novel, Glitz (1985), an Atlantic City gambling story, was his breakout in the crime genre. It spent 16 weeks on The New York Times Best Seller list, and his subsequent crime novels were all bestsellers.[13][14] In his review of Glitz, Stephen King placed Leonard in the company of Raymond Chandler, Dashiell Hammett and John D. MacDonald.[15] Leonard believed that his books during the 1980s were becoming funnier and that he was developing a style that was more free and easy. His own favorites were Freaky Deaky (1988), about ex-hippie criminals and the Dixie Mafia story Tishomingo Blues (2002).[16] Some of Leonard's characters appear in several novels, including mobster Chili Palmer, bank robber Jack Foley and the U. S. Marshals Carl Webster and Raylan Givens.[17][18]

At the time of his death his novels had sold tens of millions of copies.[19] Among film adaptations of his work are Jackie Brown, (1997), based on Rum Punch and described as an "homage to the author's trademark rhythm and pace";[19] Get Shorty (1995); Out of Sight (1998) and the TV series Justified (2010—2015) and Justified: City Primeval (2023—).[20] Nearly thirty movies were made from Leonard's novels, but for some critics his special style worked best in print.[4]

Personal life

[edit]He married Beverly Clare Cline in 1949, and they had five children together—two daughters and three sons[21]—before divorcing in 1977. His second marriage in 1979, to Joan Leanne Lancaster (aka Joan Shepard), ended with her death in 1993. Later that same year, he married Christine Kent and they divorced in 2012.[22][23] Leonard spent the last years of his life with his family in Oakland County, Michigan. He suffered a stroke on July 29, 2013. Initial reports stated that he was recovering,[24] but on August 20, 2013, Leonard died at his home in the Detroit suburb of Bloomfield Hills of stroke complications.[25] He was 87 years old.[22][23] One of Leonard's grandchildren is Alex Leonard, the drummer in the Detroit band Protomartyr.[26]

Style and influence

[edit]Commended by critics for his gritty realism and strong dialogue, Leonard sometimes took liberties with grammar in the interest of speeding the story along.[27] In his essay "Elmore Leonard's Ten Rules of Writing" he said: "My most important rule is one that sums up the 10: If it sounds like writing, I rewrite it." He also said: "I try to leave out the parts that readers tend to skip."[27]

Leonard has been called "the Dickens of Detroit" because of his intimate portraits of people from that city, though he said, "If I lived in Buffalo, I'd write about Buffalo."[10]: 90 His favorite epithet was given to him by Britain's New Musical Express: "the poet laureate of wild assholes with revolvers".[28] His ear for dialogue has been praised by writers such as Saul Bellow and Martin Amis. "Your prose makes Raymond Chandler look clumsy," Amis told Leonard at a Writers Guild event in Beverly Hills in 1998.[29] Stephen King called Leonard "the great American writer."[30] According to Charles Rzepka of Boston University, Leonard's mastery of free indirect discourse, a third-person narrative technique that gives the illusion of immediate access to a character's thoughts, "is unsurpassed in our time, and among the surest of all time, even if we include Jane Austen, Gustave Flaubert, and Hemingway in the mix."[31]

Leonard often cited Hemingway as his most important influence, but also criticized his lack of humor.[32] Still, it was Leonard's affection for Hemingway, and for George V. Higgins, that led him to will his personal papers to the University of South Carolina, where many of Hemingway's and Higgins' papers are archived. Leonard's papers reside at the university's Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.[33][34] John Steinbeck was another influence.[citation needed]

Leonard in turn had a very strong influence on a generation of crime writers that followed him, among them George Pelecanos, Michael Connelly, Dennis Lehane, and Laura Lippman.[35]

Anthony Lane praised Leonard's ear for dialogue, comparing him to Dickens and Evelyn Waugh:

"Leonard can make do with a single letter, or a blank where a letter is meant to be. 'What in the hell's a Albanian?,' a guy named Clement asks in Chapter 4 of City Primeval (1980). Typesetters may have pounced upon what they took to be a typo, but Leonard never misheard. In that respect, as in others, he was less like Hemingway—of whom he was a fan, and to whom he was often compared—than like Dickens, another city kid with his nose and ear to the ground... One proof of literary genius, we might say, is a democratic generosity toward your mother tongue—the conviction that every part or particle of speech, be it e'er so humble, can be put to fruitful use... He is gone now, but he left us a fine consolation: if you've never read him, or if you'd never heard of him until yesterday, or if you merely need a fitting way to mourn, pick up 52 Pick-Up, LaBrava, Swag, or Glitz, and tune into the voices of America—calling loud and clear, and largely ungrammatical, from Atlantic City, Miami, Hollywood, and his home turf of Detroit. Elmore Leonard got them right, and did them proud. As Clement would say, he was a author."[4]

Awards and honors

[edit]- 1984 Edgar Award for Best Mystery Novel of 1983 for LaBrava.

- 1992 Grand Master Award for Lifetime Achievement from the Mystery Writers of America[36]

- 2008 F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Award for outstanding achievement in American literature; received during the 13th Annual F. Scott Fitzgerald Literary Conference held at Montgomery College in Rockville, Maryland, United States.[37]

- 2010 Peabody Award, FX's Justified[38]

- 2012 National Book Award, Medal for Distinguished Contribution[39]

Leonard has been anthologized by the Library of America in four volumes: Westerns (Last Stand at Saber River, Hombre, Valdez is Coming, Forty Lashes Less One and eight short stories); Four Novels of the 1970s (Fifty-Two Pickup, Swag, Unknown Man No. 89, The Switch); Four Novels of the 1980s (City Primeval, LaBrava, Glitz, Freaky Deaky) and Four Later Novels (Get Shorty, Rum Punch, Out of Sight, Tishomingo Blues and the short story "Karen Makes Out".)[40]

Works

[edit]Novels

[edit]Leonard also contributed one chapter (the twelfth of thirteen) to the 1996 Miami Herald parody serial novel Naked Came the Manatee (ISBN 0-449-00124-5).

Collections

[edit]| Year | Collection | ISBN |

|---|---|---|

| 1998 | The Tonto Woman and Other Western Stories | ISBN 0-385-32387-5 |

| 2002 | When the Women Come Out to Dance Later reprint retitled Fire in the Hole |

ISBN 0-060-58616-8 |

| 2004 | The Complete Western Stories of Elmore Leonard | ISBN 0-060-72425-0 |

| 2006 | Moment of Vengeance and Other Stories | ISBN 0-060-72428-5 |

| 2006 | Blood Money and Other Stories | ISBN 0-06-125487-8 |

| 2006 | Three-Ten To Yuma and Other Stories | ISBN 0-06-133677-7 |

| 2007 | Trail of the Apache and Other Stories | ISBN 0-06-112165-7 |

| 2009 | Comfort to the Enemy and Other Carl Webster Stories | ISBN 0-297-85668-5 |

| 2014 | Charlie Martz and Other Stories: The Unpublished Stories of Elmore Leonard | ISBN 0-297-60979-3 |

Short stories

[edit]| Year | Story | First appearance | Film adaptation |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1951-12 | "Trail of the Apache" | Argosy | |

| 1952-05 | "Apache Medicine" | Dime Western Magazine | |

| 1952-09 | "You Never See Apaches..." | Dime Western Magazine | |

| 1952-10 | "Red Hell Hits Diablo Canyon" | 10 Story Western Magazine | |

| 1952-11 | "The Colonel's Lady" | Zane Grey's Western | |

| 1952-12 | "Law of the Hunted Ones" | Western Story Magazine | |

| 1952-12 | "Cavalry Boots" | Zane Grey's Western | |

| 1953-01 | "Under the Friar's Ledge" | Dime Western Magazine | |

| 1953-02 | "The Rustlers" | Zane Grey's Western | |

| 1953-03 | "Three-Ten to Yuma" | Dime Western Magazine | 1957 – 3:10 to Yuma 2007 – 3:10 to Yuma |

| 1953-04 | "The Big Hunt" | Western Story Magazine | |

| 1953-05 | "Long Night" | Zane Grey's Western | |

| 1953-06 | "The Boy Who Smiled" | Gunsmoke | |

| 1953-08 | "The Hard Way" | Zane Grey's Western | |

| 1953-09 | "The Last Shot" | Fifteen Western Tales | |

| 1953-10 | "Blood Money" | Western Story Magazine | |

| 1953-10 | "Trouble at Rindo's Station" | Argosy | |

| 1954-10 | "Saint with a Six-Gun" | Argosy | |

| 1955-02 | "The Captives" | Argosy | 1957 – The Tall T |

| 1955-08 | "No Man's Guns" | Western Story Roundup | |

| 1955-09 | "The Rancher's Lady" | Western Magazine | |

| 1955-12 | "Jugged" | Western Magazine | |

| 1956-04-21 | "Moment of Vengeance" | Saturday Evening Post | |

| 1956-09 | "Man with the Iron Arm" | Complete Western Book | |

| 1956-10 | "The Longest Day of His Life" | Western Novel and Short Stories | |

| 1956-11 | "The Nagual" | 2-Gun Western | |

| 1956-12 | "The Kid" | Western Short Stories | |

| 1958-06 | "The Treasure of Mungo's Landing" | True Adventures | |

| 1961 | "Only Good Ones" | Western Roundup | Later expanded to the novel and adapted as Valdez is Coming |

| 1982 | "The Tonto Woman" | Roundup | 2007 – Academy Awards nominated Live Action Short |

| 1994 | "Hurrah for Captain Early!" | New Trails | |

| 1996 | "Karen Makes Out" | Murder For Love – Delacorte Press 1996 | First episode in Karen Sisco TV series |

| 2001 | "Fire in the Hole" | ebook (ISBN 0-062-12034-4) | 2010 – TV series Justified |

| 2001 | "Chickasaw Charlie Hoke" | Murderers' Row: Original Baseball Mysteries[41] | |

| 2005 | "Louly and Pretty Boy" | Dangerous Women - Mysterious Press 1996 | |

| 2012 | "Chick Killer" | McSweeney's - Issue 39 |

Screenplays

[edit]| Year | Title | Director | Co-writers |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | The Moonshine War | Richard Quine | |

| 1972 | Joe Kidd | John Sturges | |

| 1974 | Mr. Majestyk | Richard Fleischer | |

| 1980 | High Noon, Part II (TV) | Jerry Jameson | |

| 1985 | Stick | Burt Reynolds | Joseph Stinson |

| 1986 | 52 Pick-Up | John Frankenheimer | John Steppling |

| 1987 | The Rosary Murders | Fred Walton | William X. Kienzle & Fred Walton |

| Desperado (TV Movie) | Virgil W. Vogel | ||

| 1989 | Cat Chaser | Abel Ferrara | James Borelli |

Audiobooks

[edit]Nearly all of Leonard's novels have been performed as audiobooks. A number of them (including The Big Bounce, Be Cool and The Tonto Woman) have been recorded more than once resulting in over 60 English-language audiobook versions of his novels.[42] Many of the earlier recordings were abridgements, the last of which was Pagan Babies (2000) read by Steve Buscemi. Certain narrators have dominated the Elmore Leonard oeuvre, notably Frank Muller (11 audiobooks), Grover Gardner aka Alexander Adams (7), George Guidall (5), Mark Hammer (5), and Joe Mantegna (5). Other notable Leonard narrators include Liev Schreiber, Neil Patrick Harris, Tom Wopat, Arliss Howard, Joe Morton, Taye Diggs, Brian Dennehy, Bruce Boxleitner, Tom Skerritt, Robert Forster, Dylan Baker, Paul Rudd, Keith Carradine, Ed Asner, and Henry Rollins.[42][43]

Nonfiction

[edit]- 10 Rules of Writing (2007)

- Foreword to Walter Mirisch's book I Thought We Were Making Movies, Not History

Adaptations

[edit]Twenty-six of Leonard's novels and short stories have been adapted for the screen (19 as motion pictures and another seven as television programs).

Film

[edit]Numerous Leonard novels and short stories have been adapted as films including Get Shorty (1990 novel, 1995 film), Out of Sight (1996 novel, 1998 film) and Rum Punch (1992 novel, 1997 film Jackie Brown). The novel 52 Pickup was first adapted very loosely into the 1984 film The Ambassador (1984), starring Robert Mitchum and, two years later, under the slightly altered 52 Pick-Up title starring Roy Scheider. Leonard has also written several screenplays based on his novels, plus original screenplays such as Joe Kidd (1972). The film Hombre (1967), starring Paul Newman, was an adaptation of Leonard's 1961 eponymous novel. His short story "Three-Ten to Yuma" (March 1953) and novels The Big Bounce (1969) and 52 Pickup (1974) have each been filmed twice.

Other novels filmed include:

- The Tall T (with Randolph Scott) (from "The Captives")

- 3:10 to Yuma (with Glenn Ford and Van Heflin)

- Hombre (with Paul Newman)

- Mr. Majestyk (with Charles Bronson)

- Jackie Brown (Pam Grier, Samuel L. Jackson, Robert De Niro) from Rum Punch

- The Big Bounce (with Ryan O'Neal)

- Valdez Is Coming (with Burt Lancaster)

- 52 Pick-Up (with Roy Scheider, Ann Margaret)

- Stick (with Burt Reynolds)

- The Moonshine War (with Alan Alda and Patrick McGoohan)

- Last Stand at Saber River (with Tom Selleck)

- Gold Coast (with David Caruso)

- Glitz (with Jimmy Smits)

- The Ambassador (Robert Mitchum, Rock Hudson, Ellen Burstyn)

- Cat Chaser (with Peter Weller)

- Out of Sight (George Clooney, Jennifer Lopez, Don Cheadle)

- Touch (with Christopher Walken)

- Pronto (with Peter Falk)

- Be Cool (with John Travolta, Harvey Keitel, Uma Thurman)

- The Big Bounce (with Morgan Freeman, Owen Wilson, Gary Sinese)

- Killshot (Diane Lane, Mickey Rourke).

- Get Shorty (with John Travolta, Gene Hackman, Danny Devito)

- Freaky Deaky (with Christian Slater)

- Life of Crime (Jennifer Aniston) (from The Switch)

- 3:10 to Yuma (with Christian Bale, Russell Crowe, Peter Fonda)

- Border Shootout (with Glenn Ford) (from The Law at Randado)

- Split Images (with Gregory Harrison, Rebecca Jenkins)

- The Arrangement (with Bryan Greenberg) (from "When the Women Come Out to Dance")

Quentin Tarantino has optioned the right to adapt Leonard's novel Forty Lashes Less One (1972).[44]

Television

[edit]- In 1992, Leonard played himself in a script he wrote and, with actor Paul Lazar dramatizing a scene from the novel Swag, appeared in a humorous television short about his writing process which aired on the Byline Showtime series on Showtime Networks.

- The 2010–15 FX series Justified was based around the popular Leonard character U.S. Marshal Raylan Givens from the novels Pronto, Riding the Rap, the eponymous Raylan, and the short story "Fire in the Hole".

- The short-lived 1998 TV series Maximum Bob was based on Leonard's 1991 novel of the same name. It aired on ABC for seven episodes and starred Beau Bridges.

- The TV series Karen Sisco (2003–04) starring Carla Gugino was based on the U.S. Marshall character from the film Out of Sight (1998) played by Jennifer Lopez.

- The 2017 Epix series Get Shorty is based on the novel of the same.[45]

References

[edit]- ^ Itzkoff, Dave (September 30, 2009). "Pen Lifetime Award For Elmore Leonard". The New York Times.

- ^ Bosman, Julie (September 19, 2012). "Elmore Leonard to Be Honored by National Book Foundation". The New York Times.

- ^ "For Distinguished Contribution to American Letters, National Book Foundation, medal, 2012". archives.library.sc.edu. 2012.

- ^ a b c d Lane, Anthony (August 21, 2013). "The Dutch Accent: Elmore Leonard's Talk". The New Yorker. Archived from the original on July 12, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ Ells, Kevin (January 31, 2011). "Elmore Leonard Jr.". Encyclopedia of Louisiana. Louisiana Endowment for the Humanities (published August 21, 2013). Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Masters, Kristin (August 20, 2013). "Remembering Elmore Leonard". Books Tell You Why.

- ^ "U.S. crime writer Elmore Leonard dead at 87". Today. August 20, 2013.

- ^ Jesse Thorn (July 3, 2007). "Podcast: TSOYA: Elmore Leonard". Maximum Fun (Podcast). Archived from the original on January 6, 2018. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ a b "Elmore Leonard > About the Author". Random House. Archived from the original on March 25, 2015. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ a b Challen, Paul C. (2000). Get Dutch! : a biography of Elmore Leonard. Toronto: ECW Press. ISBN 978-1550224221. OCLC 44674355.

- ^ Ward, Nathan (May 16, 2018). "Elmore Leonard's gritty westerns". Crimereads. Archived from the original on May 1, 2020. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Mitgang, Herbert (October 23, 1993). "Novelist discovered after 23 books". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 25, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ "I am glad, I am not a screenwriter". British Film Institute. May 9, 2006. Archived from the original on December 5, 2017. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ Acocella, Joan (September 24, 2015). "The Elmore Leonard Story". The New York Review of Books. Archived from the original on November 1, 2019. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ King, Stephen (February 10, 1985). "What Went Down When Magyk Went Up". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 7, 2018. Retrieved December 2, 2018.

- ^ McGilligan, Patrick (March 30, 1998). "Elmore Leonard interviewed by Patrick McGilligan : On writing and movies". Film Comment. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ "Elmore Leonard". fantasticfiction.com. Archived from the original on April 19, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ "The 10 best Elmore Leonard stories". rogerpacker.com. August 27, 2013. Archived from the original on March 28, 2019. Retrieved December 5, 2018.

- ^ a b Hinds, Julie (August 21, 2013). "Novelist elevated crime thriller, mastered dialogue". Detroit Free Press. p. A1.

- ^ "Elmore Leonard, writer of sharp, colorful crime stories, dead at 87 - CNN.com". CNN. Archived from the original on February 1, 2019. Retrieved August 25, 2013.

- ^ Leonard, Elmore (2009). Comfort to the enemy and other Carl Webster tales. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0297856689. OCLC 302068307. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Whitall, Susan (August 20, 2013). "Elmore Leonard, the 'Dickens of Detroit,' wrote with gritty flair". Entertainment. The Detroit News. Archived from the original on August 20, 2013. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ a b Stasio, Marilyn (August 20, 2013). "Elmore Leonard, Who Refined the Crime Thriller, Dies". Books. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ Whitall, Susan (August 5, 2013). "Elmore Leonard in hospital recovering from stroke". Entertainment. The Detroit News. Archived from the original on August 24, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ "Photos: Elmore Leonard dies". Arizona Daily Star. August 20, 2013. Archived from the original on August 22, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Lipez, Zachary (December 23, 2015). "Second Impressions of Protomartyr". Vice. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b Leonard, Elmore (July 16, 2001). "Writers on Writing; Easy on the Adverbs, Exclamation Points and Especially Hooptedoodle". Arts. The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved August 20, 2013.

- ^ The Telegraph, 20 August 2013 Archived November 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved January 22, 2017

- ^ Leonard, Elmore (January 23, 1998). "Martin Amis interviews Elmore Leonard" (PDF) (Interview). Interviewed by Amis, Martin. Archived from the original (PDF) on April 9, 2013. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ King, Stephen (February 1, 2007). "The Tao of Steve". Entertainment Weekly. Archived from the original on March 15, 2011. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ Rzepka, Charles (2013). Being Cool: The Work of Elmore Leonard. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 21. ISBN 9781421410159.

- ^ Mark Lawson, "Best-selling novelist Elmore Leonard, master of verbal tics and black humour" Archived November 15, 2020, at the Wayback Machine, The Guardian, August 20, 2013.

- ^ "Elmore Leonard's Papers (and Hawaiian Shirts) Go to University of South Carolina". October 16, 2014. Archived from the original on May 11, 2015. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "Elmore Leonard archive goes to South Carolina". October 15, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ McClurg, Jocelyn and Carol Memmott (August 20, 2013). "Author Elmore Leonard dies at 87". USA Today. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved May 21, 2019.

- ^ "Edgar Award Winners and Nominees Database". Mystery Writers of America. search using surname Leonard. Archived from the original on October 22, 2014. Retrieved August 21, 2013.

- ^ "Past Honorees". cms.montgomerycollege.edu. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved May 12, 2016.

- ^ "2010 Peabody Recipients". Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved August 22, 2013.

- ^ Flood, Alison (September 20, 2012). "Elmore Leonard to be honoured by National Book Foundation". Books. The Guardian. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ "Elmore Leonard". Library of America.

- ^ Penzler, Otto, ed. (2001). Murderers' Row Original Baseball Mysteries (First ed.). CA: New Millennium Entertainment. ISBN 978-1893224254.

- ^ a b "Elmore Leonard audiobooks". Audible.

- ^ Stim, Richard (August–September 2007). "Have I told you about my Elmore Leonard audiobook collection?" (PDF). AudiOpinion. AudioFile. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original (PDF) on November 26, 2012.

- ^ Kirk (August 17, 2009). "Tarantino's Lost Projects: '40 Lashes Less One'". We Are Movie Geeks. Archived from the original on November 15, 2020. Retrieved August 5, 2015.

- ^ Petski, Denise (May 16, 2017). "'Get Shorty' Gets Premiere Date On Epix; Unveils First-Look Photos". Archived from the original on November 16, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

External links

[edit]- Official website Archived February 3, 2018, at the Wayback Machine

- Elmore Leonard at IMDb

- Elmore Leonard at Find a Grave

- The Economist: 31 August 2013 Obituary Elmore Leonard, crime-fiction writer, died on August 20, aged 87

- Elmore Leonard's career

- Elmore Leonard on fantasticfiction.com

- Elmore Leonard Archive at the University of South Carolina Irvin Department of Rare Books and Special Collections.

- 1925 births

- 2013 deaths

- 20th-century American male writers

- 20th-century American novelists

- 21st-century American male writers

- 21st-century American novelists

- American crime fiction writers

- American male novelists

- American male short story writers

- American Noir writers

- American Western (genre) novelists

- Burials at Greenwood Cemetery (Birmingham, Michigan)

- Cartier Diamond Dagger winners

- Edgar Award winners

- Military personnel from Louisiana

- Military personnel from New Orleans

- Novelists from Florida

- Novelists from Louisiana

- Novelists from Michigan

- People from Bloomfield Hills, Michigan

- Seabees

- United States Navy personnel of World War II

- United States Navy sailors

- University of Detroit Jesuit High School and Academy alumni

- University of Detroit Mercy alumni

- Writers from Detroit

- Writers from New Orleans

- Writers of books about writing fiction