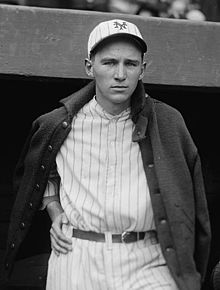

Freddie Lindstrom

| Freddie Lindstrom | |

|---|---|

| |

| Third baseman / Outfielder | |

| Born: November 21, 1905 Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

| Died: October 4, 1981 (aged 75) Chicago, Illinois, U.S. | |

Batted: Right Threw: Right | |

| MLB debut | |

| April 15, 1924, for the New York Giants | |

| Last MLB appearance | |

| May 15, 1936, for the Brooklyn Dodgers | |

| MLB statistics | |

| Batting average | .311 |

| Home runs | 103 |

| Runs batted in | 779 |

| Stats at Baseball Reference | |

| Teams | |

| Member of the National | |

| Induction | 1976 |

| Election method | Veterans Committee |

Frederick Charles Lindstrom (November 21, 1905 – October 4, 1981) was an American professional baseball third baseman and outfielder. He played in Major League Baseball (MLB) for the New York Giants, Pittsburgh Pirates, Chicago Cubs and Brooklyn Dodgers from 1924 until 1936. He was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame in 1976.

Lindstrom debuted in MLB for the Giants in 1924. In 1930, Giants manager John McGraw ranked Lindstrom ninth among the top 20 players of the previous quarter century.[1] Babe Ruth picked him as his NL all-star third baseman over Pie Traynor for the decade leading up to the first inter-league All-Star Game in 1933.[2] Modern-day statistics guru Bill James, who rates Lindstrom No. 43 on his all-time third basemen list, placed him among the top three under-21 players at that position and called the 1927 Giants infield of Lindstrom, Hornsby, Travis Jackson and Bill Terry the decade's best.[3]

In 1931, injuries – including a chronic bad back and broken leg – brought about his switch to the outfield. The Giants traded him to the Pirates before the 1933 season. He also played for the Cubs and Dodgers before he retired after 13 seasons in 1936.[4]

Early life

[edit]Lindstrom was born on November 21, 1905, on Chicago's South Side, near Comiskey Park. Lindstrom as a youngster was an ardent Chicago White Sox fan, often playing hooky from school to watch their games. He was devastated when his hero, Shoeless Joe Jackson, and other teammates were banned from baseball for allegedly throwing the 1919 World Series.[5]

Lindstrom attended Loyola Academy in Wilmette, Illinois, and was in his sophomore year when he tried out for the Chicago Cubs in 1922. He instead signed with the New York Giants, who assigned him to the Toledo Mud Hens.[6] He played for Toledo for two years with such future Giants teammates as Travis Jackson and Bill Terry.[7]

New York Giants

[edit]The Giants promoted Lindstrom to the major leagues for the 1924 season. The 18-year-old Lindstrom batted .333 in the 1924 World Series, including four hits in one game against Washington's Walter Johnson while playing errorless baseball in the field.[8] The youngest player ever in a post-season game, he was described by Johnson after the fifth game as "a wonder, easily the brightest star in this series."[9] But a bad-hop bouncer over his head in the 12th inning of the seventh game gave the series to the Senators and became an enduring moment in baseball lore. A number of later accounts of the Series called Lindstrom "the goat for his 12th-inning error." Actually, there was no error on the play, and Groh was later quoted as saying: "It wasn't Freddie's fault. It could have happened to anyone. He never had a chance to get the ball."[10] "So they won it," Lindstrom later recalled. "(Giants pitcher) Jack Bentley, who was something of a philosopher, I think summed it up after the game. ‘Walter Johnson,’ Bentley said, ‘is such a loveable character that the good Lord didn't want to see him get beat again.’"[11]

Playing in an era when fielders’ gloves were little more than padded strips of leather with a baseball-sized pocket in the palm, Lindstrom for three of the next four seasons led National League third basemen in fielding percentage. He also topped the league in assists in 1928, finishing second with 34 double plays and 506 total chances. All while posting 231 hits in both 1928 and 1930 including nine hits in a double header, a record never surpassed to this day.[12] By the time Lindstrom reached the age of 25, he had accumulated 1,186 hits, the fourth highest total for a 25-year-old player in MLB history, behind only Ty Cobb (1,433), Mel Ott (1,249) and Al Kaline (1,200).[13]

A million-dollar infield," said writer Arnold Hano of the late-1920s Giants quartet. "Fans would come early just to watch their fielding-practice magic." In an essay on Willie Mays’ famous 1954 back-to-the-plate catch off Cleveland's Vic Wertz, Hano claimed that an even more sensational play was Lindstrom's full-length, leaping grab before crashing into the outfield wall in a 1932 Giants-Pirates game that the New York Herald Tribune later called "the greatest catch ever made in the Polo Grounds."[14] During his nine seasons with the Giants, Lindstrom batted .318 (fourth on the team's all-time list in the 20th century), while demonstrating his ability to come through in the clutch with pennant-chasing hitting streaks in September 1928 that raised his average from .342 to .358 and in 1930 from .354 to .379.[15] As late as 1935 while playing center field for the Chicago Cubs, his .427 batting average during a stretch of 21 consecutive victories was credited by such Chicago newsmen as John P. Carmichael and Warren Brown as the main factor in the Cubs’ drive for the NL championship.[16]

Often referred to as "the last of the great place hitters" on McGraw teams that emphasized advancing runners into scoring position rather than relying on the long ball,[17] Lindstrom in 1931 was led to believe that he would succeed the long-time Giants manager. "We’re making that change we spoke about next year," Lindstrom, recuperating from a broken leg, said he was told by Giants’ club secretary Jim Tierney. "McGraw is going out and we want to make you manager."[18] Instead, for reasons that some traced to Lindstrom's leadership role in a player revolt against their often dictatorial manager (a charge he consistently denied, although admitting that he often spoke out against the feisty skipper nicknamed Little Napoleon), club owner Horace Stoneham chose first baseman Bill Terry to replace McGraw.[19] Although the two remained friends, Lindstrom demanded a trade, which took him to Pittsburgh in 1933. To the press, Terry said, "Fred no longer has that burst of speed he used to have."[20] Several years later, Lindstrom conceded "It was the worst mistake I ever made. If I could have just accepted that setback, it would have worked out in time. But I fouled the whole thing up -- forever."[21]

Pirates, Cubs, and Dodgers

[edit]Playing in the outfield between Lloyd and Paul Waner, Lindstrom finished second on the Pirates to shortstop Arky Vaughan by four percentage points with a .310 batting average (eighth highest in the National League), hitting 39 doubles and leading the league's center fielders with a .986 fielding average.[12]

In the 1934 season, George Gibson was fired as manager 51 games into the season with the Pirates mired in fourth place. His replacement, Pie Traynor, moved Lindstrom to left field and then to the bench after breaking his finger in a fungo game.[22] At season's end, despite fielding .990 and again outhitting Lloyd Waner while playing in 43 fewer games, Lindstrom was traded to the Chicago Cubs where he quickly became what Cubs manager Charley Grimm later called "a vital asset" in the team's 1935 league championship.[23] Starting at third base ahead of Stan Hack, he was later shifted to fill a void in center field. There, Grimm said, as boss of the outfield he allowed only seven pop flies to fall safely during that 21-game streak. He also drove in the winning run, or scored it, in seven of the games including three singles and a double off Dizzy Dean of the St. Louis Cardinals in the pennant-clinching contest. "And why isn’t Lindstrom in the Hall of Fame?" Grimm asked in a 1968 interview.[24]

After the Cubs lost to the Detroit Tigers in the 1935 World Series, however, the following January he was released and later signed by the Brooklyn Dodgers. After only 26 games and a .264 batting average, Lindstrom abruptly retired from baseball following a collision with infielder Jimmy Jordan while going for a routine pop fly. "I have been in this league 12 years," Lindstrom reportedly said, "and it never happened to me until I put on a Brooklyn uniform."[25]

In 13 years and 1,438 games played, Lindstrom compiled a .311 batting average (1,747-for-5,611), with 895 runs, 301 doubles, 81 triples, 103 home runs and 779 runs batted in. His on-base percentage was .351 and slugging percentage was .449. He hit .300 or better seven times. Lindstrom recorded six 5-hit games. He hit for the cycle on May 8, 1930. In 11 World Series games (1924 and 1935), he hit .289 (13-45) with four RBIs.

Later career and personal life

[edit]

In later years, Lindstrom managed minor league teams at Fort Smith, Arkansas, and Knoxville, Tennessee. After coaching the Northwestern University baseball team for 13 seasons, he was appointed postmaster of Evanston, Illinois, a position he held until 1972. He died nine years later and is buried with his wife, Irene, in Chicago's All Saints Cemetery.[26] The youngest of their three sons, Chuck Lindstrom, played briefly for the 1958 Chicago White Sox, walking and tripling for a perfect 1.000 batting average and on-base percentage in two plate appearances.[27]

Freddie Lindstrom died at Mercy Hospital in Chicago on October 4, 1981, and was buried at All Saints Cemetery.[28]

Legacy

[edit]

Although many modern-day baseball historians refer to Traynor as the era's premier fielding third baseman, the Pirate Hall of Famer led the league in errors five times including 37 in 1931 and 27 in both 1932 and 1933. Lindstrom's high mark was 21 errors in both 1928 and 1930. For the seven comparable seasons that Lindstrom played third base, his fielding percentage tops that of Traynor each year.[29]

Donald Dewey and Nick Acocella (All Time All Star Baseball Book, Elysian Fields Press, 1992) list Lindstrom as the New York Giants all-time third baseman. The esteemed sportswriter, Red Smith, placed him at third base on an all-time New York all-star team that had no room for the likes of Mickey Mantle, Duke Snider or Mel Ott.[30]

John Kieran (Sports of the Times), reported the following: "Arthur Nehf was sitting in the Chicago dugout talking about the Giant hitters. He talked of Roush, Jackson, Terry and Hogan and then remarked decisively that Freddie Lindstrom was the cleverest of them all at the plate and the hardest man to fool in the clutch."[31]

Lindstrom's four hits in Game 5 of the 1924 World Series stood as the rookie record until matched by San Francisco's Buster Posey in the 2010 series.

Along with a 24-game hitting streak in 1930 and a 25-game streak in 1933, Lindstrom also ranks among the all-time top 10 in lifetime strikeouts to batting average ratio, 276 strikeouts to .311 batting average in 6,104 plate appearances. Lloyd Waner, Pie Traynor and Arky Vaughan are also on the list.[32]

Lindstrom led the league in outfield assists in 1932 and putouts in 1933. He came to the Pirates as "a strong defensive player and even better right-handed line drive hitter."[33]

The Hall of Fame's Bill Francis posted an undated article titled "Research Sheds New Light on Lindstrom's 1930 Season" that shows he batted .480 that year with runners in scoring position, the highest in Major League history. According to the Society for American Baseball Research’s Records Committee, in a publication authored by SABR Records Committee Chairman Trent McCotter, "In discussions of George Brett’s magical 1980 season, his overall .390 batting average is often mentioned alongside his .469 average with runners in scoring position, which is occasionally cited as the highest such figure in history. However, thanks to Retrosheet, we now know that Brett’s .469 figure had actually been ‘surpassed’ - fifty years earlier in 1930 by Giants’ third baseman Freddie Lindstrom, who went 59-for-123 (.480) with runners in scoring position. Lindstrom hit .379 overall that season."[34]

Lindstrom was included in the balloting for the National Baseball Hall of Fame starting in 1949, but never received more than 4.4% of the vote from the Baseball Writers' Association of America (BBWAA).[35] Former Giants teammates Terry and Frankie Frisch joined the Veterans Committee in 1967, and aided the elections of several of their former teammates, including Jesse Haines in 1970, Dave Bancroft and Chick Hafey in 1971, Ross Youngs in 1972, George Kelly in 1973, Jim Bottomley in 1974, and Lindstrom in 1976.[36][37]

Lindstrom's selection, along with some of the other selections made by Terry and Frisch, has been considered one of the weakest in some circles.[38] According to the BBWAA, the Veterans' Committee was not selective enough in choosing members.[39] Charges of cronyism were levied against the Veterans' Committee.[40] This led to the Veterans Committee having its powers reduced in subsequent years.[41] In 2001, baseball writer Bill James ranked Lindstrom as the worst third baseman in the Hall of Fame.[42] Like a number of selections by the Veterans Committee, Lindstrom's nomination was controversial. With opinions on both sides, legendary baseball writer Red Smith wrote "The present members would be pleased to welcome him into their company."[43] Frank True of the Sarasota Herald-Tribune,[44] Bob Broeg of The Sporting News,[45] and Lou O'Neill of the Long Island Press [46] were equally complimentary.

See also

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ International News Service, New York, May 7, 1930.

- ^ Babe Ruth, Christy Walsh Syndicate, July 5, 1933.

- ^ New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract, Free Press, 2001, p. 127.

- ^ Broeg, The Sporting News, March 17, 1973.

- ^ Donald Honig, The October Heroes, Simon & Schuster, 1979, p. 257–9.

- ^ "Mere Boy Is Signed By New York Giants". The Pittsburgh Press. May 19, 1922. p. 30 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Eichmann 1974, p. 6.

- ^ John Leventhal, The World Series, Black Dog Publishers, 2001, pp. 66–69.

- ^ Walter Johnson, Christy Walsh Syndicate, Oct. 9, 1924.

- ^ The Glory of Their Times, Lawrence Ritter, p. 385

- ^ Honig, The October Heroes, p. 278.

- ^ a b "Freddie Lindstrom". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ "Mike Trout isn't the fastest to 1,000 hits, but it's still a historic feat". sbnation.com. August 8, 2017. Retrieved May 28, 2024.

- ^ Hano, Arnold (1955). A Day In The Bleachers. Da Capo Press. p. 168.

- ^ Eichmann 1974, pp. 7–8.

- ^ "Grimm Calls ’35 Cubs His Best", Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1968, p.2 Sports.

- ^ Hano 1968, p. 178.

- ^ Honig, The October Heroes, pp. 266–67.

- ^ Joseph Durso, The Days of Mr. McGraw. Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1969, p. 213. Anthony J. Connor, Baseball for the Love of It, MacMillan, 1982, pp. 94–95.

- ^ Hano, Greatest Giants of Them All, p. 195.

- ^ The Hammond, La. Times, June 19, 1957.

- ^ Eichmann 1974, pp. 8.

- ^ "Grimm Calls," Chicago Tribune, September 2, 1968, p.2 Sports.[verification needed]

- ^ "Grimm Calls", p. 2 Sports.

- ^ Tot Holmes, Dodgers Blue Book, 1981, p. 34. Fred Stein, Mel Ott: The Little Giant of Baseball, McFarland & Co., 1999, p. 146.

- ^ Connor, Baseball for the Love of It, pp. 266–67. Freddie Lindstrom, SABR Encyclopedia, June 25, 2010. Freddie Lindstrom, Baseball Reference.com.

- ^ "Charlie Lindstrom". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved September 23, 2024.

- ^ "Hall of Famer Freddie Lindstrom, 75, Dies". Los Angeles Times. October 6, 1981. p. 36. Retrieved November 28, 2021 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lindstrom, Traynor Baseball Reference.com

- ^ Smith, "Sports of the Times", New York Times, January 28, 1975.

- ^ Kieran, New York Times, undated 1930.

- ^ Graham Womack, Baseball Past & Present, May 25, 2011.

- ^ Dave Finoli and Bill Rainer: The Pittsburgh Pirates Encyclopedia, 1933.

- ^ Francis, Bill. "Research Sheds New Light on Lindstrom's 1930 Season". National Baseball Hall of Fame. Retrieved May 11, 2022.

- ^ "Freddie Lindstrom Statistics and History". baseball-reference.com. Retrieved June 19, 2012.

- ^ "This Annotated Week in Baseball History: April 8–14, 1897". Hardballtimes.com. April 13, 2007. Retrieved June 18, 2012.

- ^ Jaffe, Jay (July 28, 2010). "Prospectus Hit and Run: Don't Call it the Veterans' Committee". Baseball Prospectus. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Jaffe, Jay (July 28, 2010). "Prospectus Hit and Run: Don't Call it the Veterans' Committee". Baseball Prospectus. Prospectus Entertainment Ventures, LLC. Retrieved June 11, 2012.

- ^ "Baseball Brouhaha Brewing". The Evening Independent. January 19, 1977. p. 1C. Retrieved November 3, 2011.

- ^ Sullivan, Tim (December 21, 2002). "Hall voter finds new parameters unhittable". The San Diego Union Tribune. p. D.1. Retrieved November 3, 2011.[dead link]

- ^ Booth, Clark (August 12, 2010). "The good news: Baseball Hall looking at electoral revamp". Dorchester Reporter. Retrieved December 21, 2011.

- ^ James, Bill (2001). The New Bill James Historical Baseball Abstract.

- ^ Smith, "Fred Lindstrom and the Hall of Fame", New York Times, January 31, 1975.

- ^ True, "As Son Sees Father in an Upside Down Era", Sarasota Herald-Tribune, February 10, 1973.

- ^ Broeg, "Lindy's Shrine Credential More Than Ample", The Sporting News, March 17, 1973.

- ^ O'Neill, Long Island Press, August 8, 1975.

References

[edit]- Hano, Arnold (1968). Greatest Giants of Them All.

- Eichmann, John (January 1974). Mitchell, Steve (ed.). "The Fred Lindstrom Story". Sports Scoop. Vol. 2, no. 1.

Further reading

[edit]- Faber, Charles F. "Freddie Lindstrom". SABR.

External links

[edit]- Freddie Lindstrom at the Baseball Hall of Fame

- Career statistics from Baseball Reference, or Fangraphs, or Baseball Reference (Minors), or Retrosheet

- Freddie Lindstrom at the SABR Baseball Biography Project

- Freddie Lindstrom at Find a Grave

- 1905 births

- 1981 deaths

- Brooklyn Dodgers players

- Chicago Cubs players

- Loyola Academy alumni

- Major League Baseball third basemen

- Minor league baseball managers

- New York Giants (baseball) players

- National Baseball Hall of Fame inductees

- Northwestern Wildcats baseball coaches

- Sportspeople from Evanston, Illinois

- Baseball players from Cook County, Illinois

- Pittsburgh Pirates players

- Toledo Mud Hens players

- Fort Smith Giants players

- 20th-century American sportsmen